I was rudely awakened this morning by the pain of a Charlie Horse in my right calf. I massaged the calf until the pain subsided, then lay in bed, pretending it was possible to fall back to sleep. But my mind was already whirring, thinking about the day ahead. I found myself contemplating lifelines, not just in knitting, but in my life in general. You see, just before I went to sleep last night, I dropped some stitches in the Begonia Swirl Shawl. I picked up the stitches, but they had dropped three or four rows already. I was too tired to deal with the problem, so I went to bed without resolving it. I may have to rip back the rows to fix the problem and, as usual, I have no lifelines.

In knitting, a lifeline is a spare piece of string that you run through all the stitches on your needle. You aren’t using the lifeline to work stitches, and the spare string is not connected to the working yarn of your project.. There’s a number of ways to actually create a lifeline, but the easiest way to describe its function and purpose is to say that you create a lifeline by threading your extra string onto a tapestry needle and running it underneath your knitting needle, through all the live stitches on the needle. You then leave this extra string in place, with loose ends dangling down each side of your project.

When you encounter a mistake in your knitting — which you inevitably will, since we are all human — you have four basic options for fixing the mistake. First, the laissez faire option. With this option, you do not technically fix your mistake. You alter your knitting in the place where you are so that the effect is the same as if you had correctly knitted the piece. I tend to use this option if I am knitting a swath of stockinette stitch and my stitch count is off by one or two stitches. An extra knit two together or slip slip knit if I have too many stitches on the needles, a make 1 or yarn over or knit front and back if I need to create an extra stitch or two, and no one is the wiser. Second, the surgical option. Intentionally drop down the offending stitches by a few rows and rework them correctly. I have used this option to fix cables, to fix a stitch that was worked as a purl when it should have been a knit or vice versa, and to fix lace patterns. Third, the slow and steady option. Tink back to where the mistake occurred and work the stitches correctly. If a mistake happened one or two rows back and you do not have many stitches on the needles, tinking back will not take a lot of time and may be your best choice for fixing the mistake. Finally, the nuclear option. Take the knitting needle out of your work, rip back rows of knitting until you are past the point of your mistake, slide the live stitches back onto your needle, and work forward again from that point. I used this option last year while knitting an Icarus shawl. I was running out of yarn and the yarn I was using was no longer available so I could not buy another skein. I had to use a contrast yarn, but in order to do that, I had to rip back to a point in the pattern where transitioning to a new color made sense rather than looking random.

A lifeline only helps you if you need to use the nuclear option. The lifeline tells you that your knitting is fine before that point, so you don’t need to rip back any further. It also holds your live stitches while you slide your knitting needle back into the stitches, so that you don’t accidentally drop stitches in the process. It is easy to drop stitches while picking back up a row. As you pick up stitches, the yarn from the next live stitch is pulled into the stitch you just slid onto the needle. If you aren’t careful, you can pull too much and all of the yarn from that next live stitch will slide right out, dropping that live stitch.

I almost never use lifelines. When I encounter a mistake in my knitting, I attempt to solve the mistake by following the options in the order I listed them above: laissez faire, surgical, slow and steady, nuclear. I have faith in my ability to solve knitting mistakes without resorting to the nuclear option unless it is absolutely necessary. I have this faith because I can read my knitting. I can look at the stitches and see what I did. Three rows down, that’s a slip slip knit, then nine knit stitches, then knit two together, then a yarn over, etc. This means I can always orient myself in the pattern in order to recognize exactly where I made a mistake, which makes the first three options easier to execute. It also means that if I go with the nuclear option, I can recognize which pattern row I am on when I start reknitting. I also have faith in my ability to understand the pattern of the pattern. When I am working a pattern, I am always trying to understand exactly how it is going to work. I have never designed a knitting pattern, but it is something I would like to do at some point in the future. So I pay close attention to what is happening in a pattern when I knit it. I spend time reading the pattern, considering why the designer made particular choices and visualizing exactly how the rows work together. This also helps me to recognize what should be happening in the project, so that I recognize mistakes earlier. Recognizing mistakes early means the first three options are more viable, reducing the need for pursuing the nuclear option.

The only time I have used the nuclear option is in lace projects. Even though I can recognize where I am in the project and exactly where I made a mistake, fixing mistakes in lace is not always easy. I can and have dropped stitches back several rows and fixed them even with yarn overs and knit two togethers. But doing this often means the stitches get tight, messing up my gauge. Perhaps this can be fixed in blocking, but perhaps not. If the problem is back more than three or four rows, I might use the nuclear option. Or a combination of the nuclear option with the other options — I could rip back only one or two rows, then use the other methods to fix the mistake. Ripping back a little bit makes it easier to see and solve the problem and saves me from having to reknit too many 600 or 700 or 890 (in the case of the Begonia Swirl Shawl) stitch rows.

Turns out, the Begonia Swirl Shawl required the nuclear option. My mistake occurred three rows back, and is repeated across the row. Since it occurs on the border of the edge motif, it is a very visible error and throws off the alignment of the motif as I move forward. This kind of problem can only be fixed by ripping all the way back past the error and reknitting it correctly.

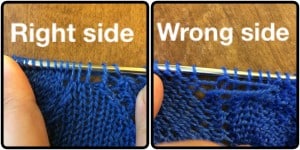

Most of the lace projects I have completed had rest rows between the pattern rows. This usually means you purl straight across the wrong side of the work. Your yarn overs and knit two togethers and all the other complicated work of lace happens on the right side of the work. When I am knitting this type of lace, I do not use a lifeline. I see every purl row as a lifeline. If I have to use the nuclear option, I rip back so that I am picking my stitches back up on a purl row.

I pick the live stitches up with a needle that is one or two sizes smaller than the size I am using for the project — a trick I learned from Marney, the fabulous proprietor of my local yarn store, when I arrived at her shop with my Icarus shawl, in a panic because I wanted to have it done to wear to an event in two days and I knew I didn’t have enough yarn — which minimizes the possibility of dropping a stitch.

If I do drop a stitch while picking up, I slide the dropped stitch onto the needle so it doesn’t drop any further, then fix it as I work across my first row of knitting, after the stitches are securely on the needle again. I also pick up stitches without worrying about their orientation on the needle. I pick each stitch up in whatever way it is easiest to get it back on the needle. This means that if I”m not careful, I will end up with many twisted stitches. I examine each stitch as I work the first row of knitting and correct its orientation on the needle if necessary to avoid twisted stitches.

Given my approach to rectifying knitting mistakes, the only time I use a lifeline in my knitting is when I am working complicated lace. For me, this means lace that has no rest rows. Yarn overs, decreases, and other stitch manipulations are happening with equal frequency on both sides of the work. When this is the case, using the first two options is difficult and often unwise. Tinking back is possible, but when you have hundreds of stitches on the needles it is going to take you a lot of time; tinking back through decreases can cause also cause you to drop stitches, compounding your problem (this is exactly what caused my current problem with the Begonia Swirl Shawl. I was trying tink back to the beginning of the row and did not pick up all the stitches on a knit three together). Ripping back to a lifeline is often the quickest option for fixing complicated lace.

As I lay in bed contemplating my options for the Begonia Swirl Shawl, I started thinking about lifelines in my general life, not just my knitting life. Over the last several years, Chris and I have gone through a series of challenging events. It all started in 2007, when I left my full-time secretarial job to become a full-time law student. First there was three years of law school, followed by several weeks of studying for the bar exam (which I passed on the first try), followed by a year of obtaining an LLM degree at a school two hours drive from our house, followed by a year of mostly pro bono work that consumed all my time (including several consecutive months of 80 – 100 hours a week of work where I was sleeping maybe 20 hours a week), followed by 14 family members dying in 18 months. I haven’t worked now for a bit more than two years as the first of the family deaths occurred right as I was leaving the pro bono work and Chris and I decided the best use of my time was to support family through the transition after the death. Of course, we had no idea at the time how many deaths there would be, and how much support would be required or how long support would be necessary. For the last year and a half, the company Chris works for has been working through a series of transitions and restructuring, making his job situation stressful and unstable.

Our lives have been unmade and remade multiple times in the last few years due to this series of events. We have used all the options for approaching the challenges and obstacles that these events threw in our path. Some days, the lassiez faire attitude is the only thing that keeps us going. Tomorrow is another day. We can not allow the problems of the past keep us from moving forward, so we make a small, quick change and just keep going. Sometimes, the surgical approach is the best. We drop a few things out of our lives — extra responsibilities so that our time is free to use in a different way or extra expenditures so we can afford the plane tickets for me to fly to New Jersey every month to help family members. When we have a little extra time, we carefully tink back. In my life, I think of this as the bigger systemic changes we have made or are making in our lives. These changes are slow and careful, and often invisible to others, because making systemic changes means that the outward fabric looks smooth and flowing. Decluttering is one of the systemic changes we have been making. Sorting through the accumulated detritus of others’ lives incited us to evaluate everything that is important to us, and to think about what we really need and want in our lives. This means everything from the physical objects to the television we watch to the people we have in our lives.

And then there’s the nuclear option. In some ways, I feel like the nuclear option describes what has happened to us over the last few years. Our life, the life we expected, was ripped out whether we wanted it to be or not. On the other hand, the reevaluation of our lives that has flowed inexorably from the events of the past few years has opened up the possibility of an intentional nuclear option. I mean by this a reshaping and remaking of our lives on every level. Every choice feels open: where do we want to live; where, how, and what do I want to do for work; how do we want to spend our free time; what relationships do we want to nurture or terminate.

What are our lifelines in this situation? We have the education, skills, talents, and experience we have accumulated throughout our lives. These are more than just lifelines. They are lifelines in the sense that they hold our foundation in place so that we can remake our future without dropping back further. But they are also the lenses through which we look at the world, which let us recognize where we are and the pattern within the pattern, so that we have options for moving forward. In another sense, our skills, talents, and experience are also our working yarn, which we will pick up and make into our future. Chris and I are lifelines to each other. We know that we are on the same team. The success of one of us is attributable to the whole, and would not be possible without the other. Our financial resources are a lifeline. Chris’s salary has been more than sufficient to provide for our daily needs. We have relatively little debt and enough savings that we would not be in an immediate crisis if the transitions at Chris’s work eventually led to the company laying him off. Relationships are a lifeline. We are blessed to have good relationships with our families. We have not actively maintained most of our friendships because we just did not have the spoons. But we do have a large circle of acquaintances, and now that we have a few more spoons we can start refurbishing those neglected bridges.

Our single biggest obstacle is fear. This is compounded by a level of weariness with uncertainty and change. So much has been taken from us without our consent that it is sometimes hard to wrap our minds around letting go voluntarily. So here we sit, looking at the messy tangle the last few years have worked into our lives and contemplating. How will we choose to turn this work back into magnificent art? I do not know the answer to this question yet, but thinking about our lifelines makes me cautiously optimistic. We have resources that we can rely upon to get there from here.

1 thought on “Lifelines”