We finished the warping board three weeks ago, but I haven’t had a chance to use it yet. I was waiting to blog about it so that I could have a picture of warp measuring in progress, but it looks like it’ll be another week before I get to measuring out the warp, so I decided to go ahead and blog the process of making the warping board!

Designing the Warping Board

At the beginning of March, I went to a beginning weaving class at the home of one of the Guild members. Part of the materials for the class included written instructions on how to use a warping board (we got a demo also). When the instructor learned that my husband was going to build me a warping board, she gave me an extra sheet on how to build one. Those instructions were for a 14-yard warping board that you would hang on the wall or put on an easel or otherwise prop up in order to use. I knew that wasn’t what I wanted, but that sheet provided my starting point. I used it mostly to determine the size and placement of the dowels. When I designed my warping board, I knew I wanted:

- The ability to make long warps

- To easily disassemble the board for storage and reassemble it for use

- Built in support while it was in use (no hanging on doors or walls)

- The warping board to be at the height that was most comfortable for me to use — I’m only 5’2″, and I didn’t want to have to raise my arms so high that I was quickly fatigued while wrapping long and wide warps.

- The cross formed on the vertical posts, not the horizontal posts

- According to the instructor at the beginning weaving class, it is more comfortable to use the warping board in this orientation, and it is easier to see if you make a mistake.

- Provides greater flexibility in the length of warp the board can accomodate.

While contemplating these characteristics, I remembered the blocking frame my husband built me for my birthday several years ago. This is a large frame, with nails driven in every inch or so. You use it by wrapping cotton yarn around the nails and through the perimeter of your lace, adjusting tension before tying off.

This frame is huge, and I considered using it as a warping board. Since it wasn’t intended as a warping board, it has some features that make it difficult to use it for that purpose. The length isn’t measured out for warping, the nails are too short and have a head on them that will make it difficult to get a warp off, and there’s no measured area for a cross. It does however, come apart for storage, and it has feet. The feet have slots in them and the vertical post slide into those slots for when the blocker is in use and out of the slots for storage.

As long as the vertical posts of the warping board were the same dimensions as the vertical posts on the blocker, we could use the feet interchangeably. Coincidentally, the size of the frame on the warping board instructions I was given, was exactly the same as the size of the vertical posts on the blocker. Voila! Support problem solved.

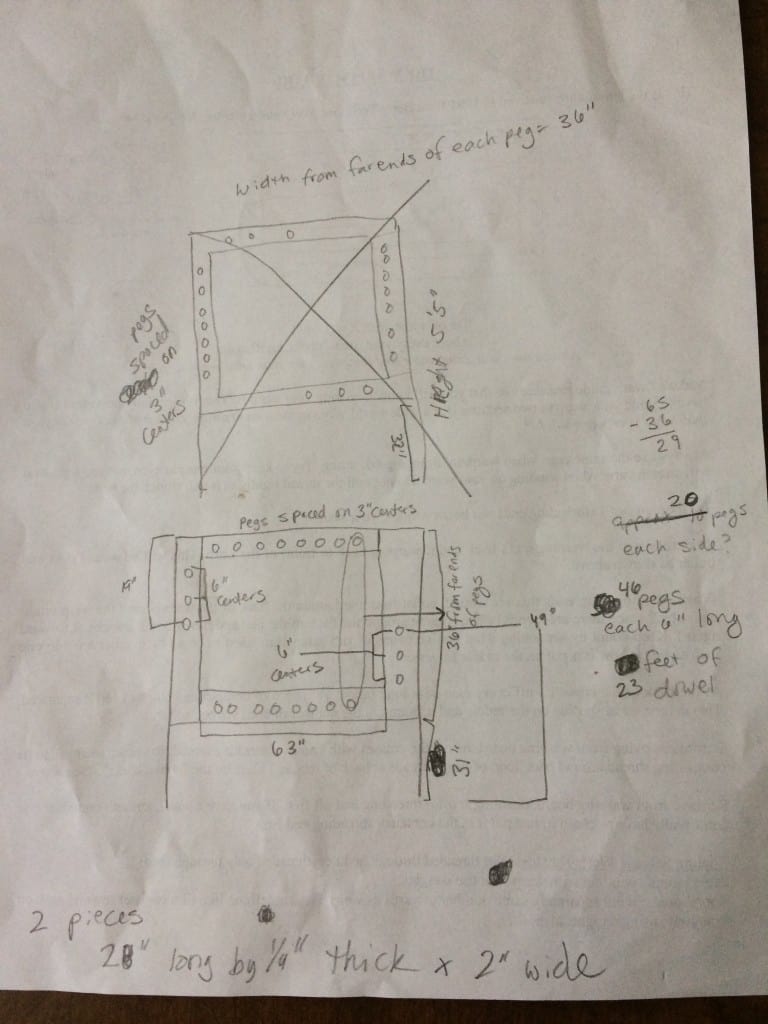

To determine the overall height of the warping board, I pretended I was holding a strand of yarn and held my arm at the lowest level I could comfortably reach. I measured the distance from the floor to my hand. I then reached up as high as I could comfortably reach and measured the distance from the floor to my hand. The difference between the two was more than the 36″ distance that I wanted between the top and bottom of the warping board. I decided to use the bottom as the starting point rather than the top, just in case my ability to reach up is ever impaired. Once I had those two measurements, I was able to combine that information with the information in the instructions I was given, and provide my husband with a drawing of the warping board.

It’s not a work of art, but it was sufficient for the purpose! I didn’t realize until it was finished that I forgot to account for the height of the feet when determining the length of the vertical supports. As a result, the finished warping board is 2″ taller than I expected. This is easy enough to fix, if it turns out to be a problem. I want to use the warping board once before I decide to trim 2″ off the bottom of the vertical posts.

Materials & Cost

1 – 2″ x 4″ x 8′ board. If you want to make feet like I have, you’ll need a second 2×4 (US$2.50 each)

7 – 5/8″ x 4′ dowels. (US$2.50 each)

scrap piece of 1″ x 8″ board. Our scrap piece was about 18″ long (free, since it was just hanging out in our garage, leftover from another project)

8 – 5/16″ 18 thread brass wood insert nuts (idk if these come in various lengths; the ones we used were about 1/2″ long) (US$0.24 each)

8 – 5/16″ 18 thread 2″ long hex bolts (US$0.22 each plus tax = $1.89 total).

8 – 5/16″ washers (approximately US$0.90; we bought a box of 50 for US$5.58, so about US$0.11 / washer)

NOTE: Using regular bolts, like we did, means that the warping board will be assembled and disassembled with a wrench. The big box hardware stores did not have any handles or knobs attached to an appropriately sized bolt. However, such things do exist and can be found at specialty woodworking supply shops, or maybe online. Our local woodworking supply is 1/2 hour away and we weren’t heading that direction for any other reason. We decided to use regular bolts now, but I will probably switch those out for a knob or handle next time we are at the woodworking shop. Then I will be able to assemble and disassemble the warping board with just my hand!

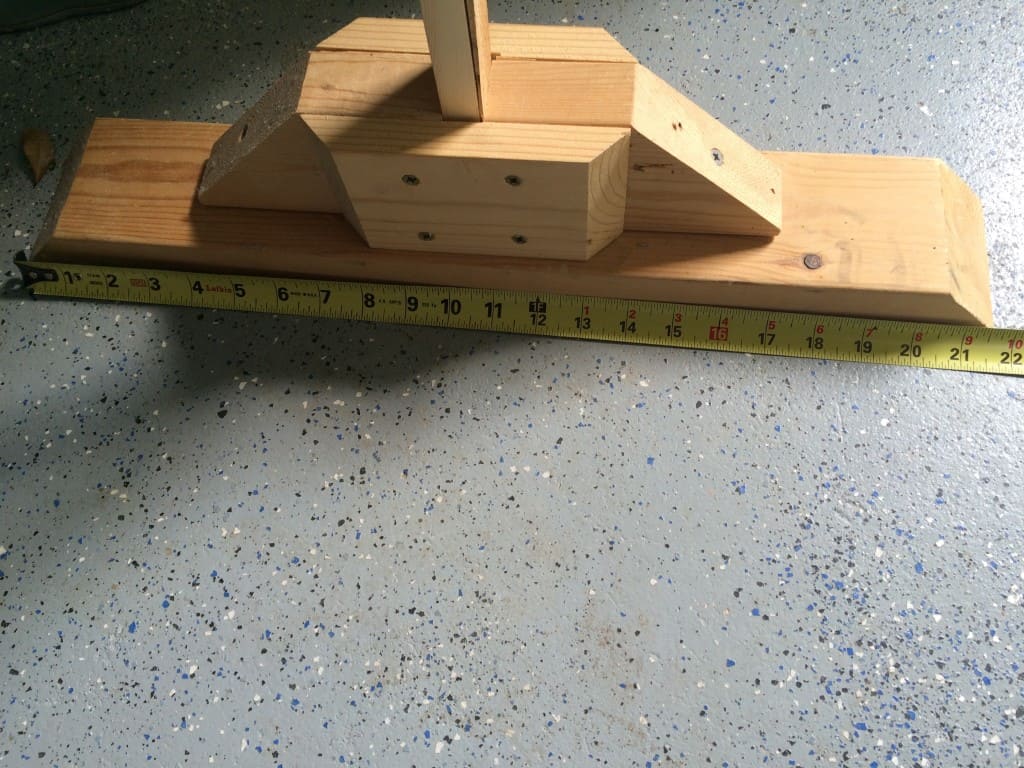

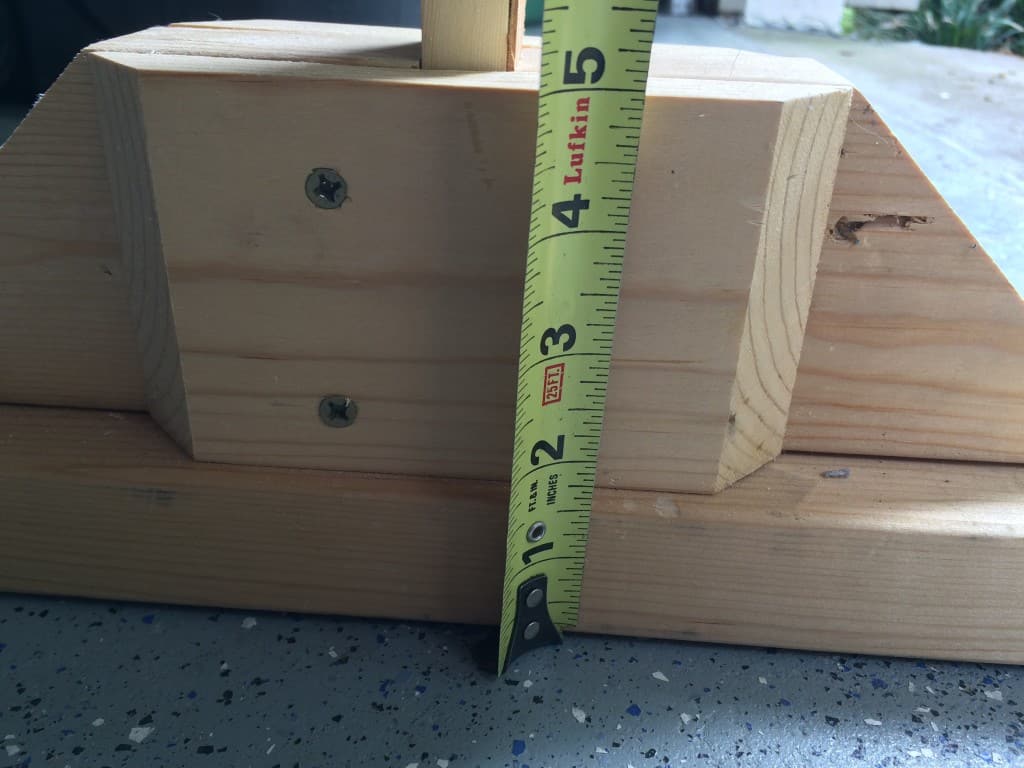

NOTE 2: Since the feet were made as part of another project, this blog post does not include instructions on how to make them or include the materials on the list. If you plan to make the feet, you will need another 2 x 4 and a few screws. You can use the pictures and dimensions above to figure out how to make them.

Total cost was about US$20; another 2 x 4 and screws for the feet will cost you another US$5 or less.

Building the Warping Board

The frame of the warping board is made with 1″ x 2″ lumber, so the first thing Chris did was rip the 2″ x 4″ into four 1″ x 2″ x 8′ pieces.

One 2″ x 4″ was exactly the right size; we were left with one long wood shaving!

Each 1″ x 2″ piece was then cut to the appropriate length. The leg pieces are each 67″ long and the horizontal pieces are each 63″ long. Before cutting the holes for the pegs, Chris had to figure out the placement of the screws and bolts that hold the warping board together. Unfortunately, I do not have good pictures of this part of the process. Since I wanted to be able to disassemble the warping board for storage, we couldn’t just screw the horizontal and vertical pieces together. Instead, we used triangular supports in the corners. These triangular supports were cut from the scrap piece of 1″ x 8″ wood that is listed in the materials section.

The supports are permanently screwed into the horizontal pieces, but bolted to the vertical pieces. Chris had to determine the placement of the screws and pegs before cutting the holes for the pegs because we didn’t want to cut a peg hole at the spot where the screw or bolt goes into the board. He drilled the holes for the screws, but did not actually screw the triangular support piece onto the horizontal board until later. While he was at it, he drilled the holes for the bolts. The bolts go all the way through the vertical support and screw into the brass wood insert nuts, which are in the triangular support piece. To get the brass wood insert nuts into the triangular support piece, Chris drilled holes slightly smaller than the nuts and then screwed the nuts into the hole. There’s different styles of insert nuts. Some are hammered in rather than screwing, but Chris says he prefers the kind that screw in because they seem stronger.

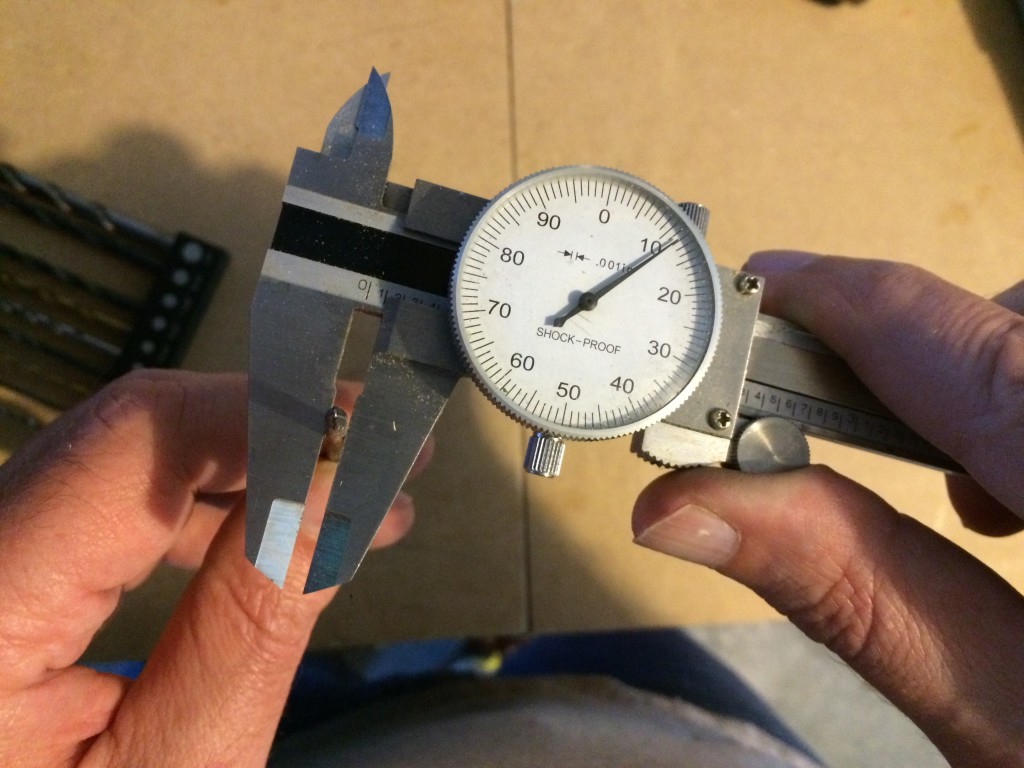

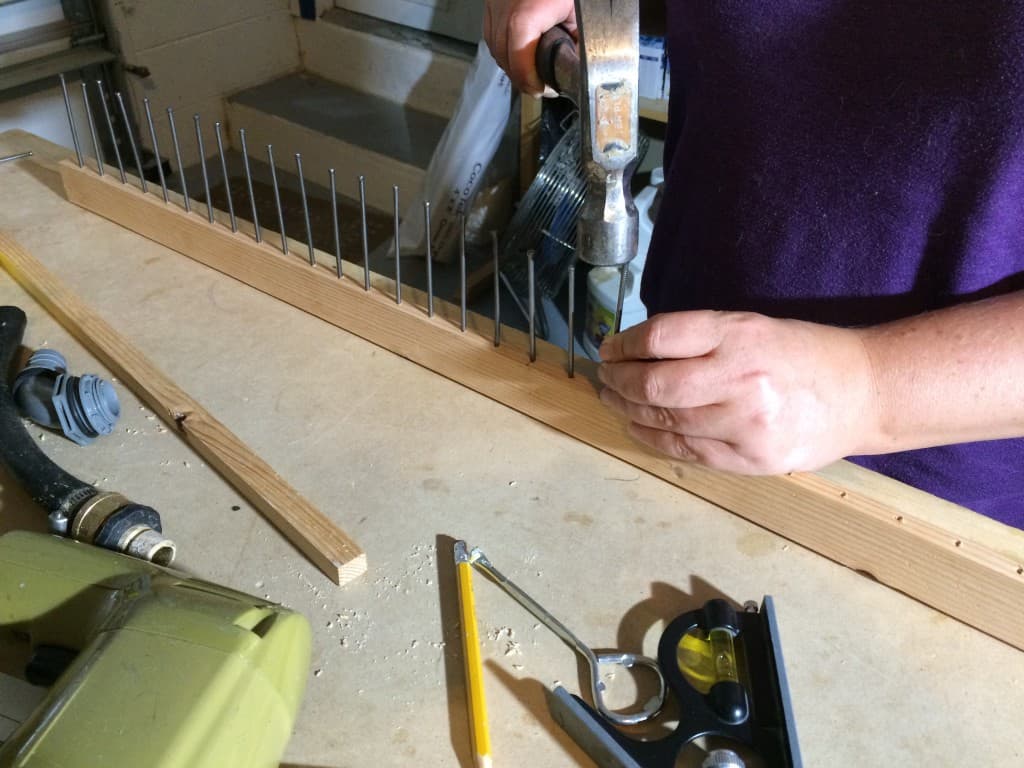

Once he got it all marked, Chris used the drill press to cut the holes for the pegs. These holes are not cut all the way through the board; they are about 1/2″ deep. While this process could be done with a hand drill rather than a drill press, the drill press has settings to assure that each hole is the same depth. On the horizontal pieces, the pegs are placed on 3″ centers (measuring from the center of one peg to the center of the adjacent peg is 3″). On the vertical pieces, there’s only 3 pegs, placed on 6″ centers, so that you can do a cross on either side if you wish. On each side, one peg is placed so that it is halfway (18″) between the two horizontal rows of pegs. On one side the other two pegs are placed upwards from the central peg; on the other side, the two pegs are placed downwards from the central peg.

While Chris was drilling the peg holes, I sanded the dowel rods that we used for the pegs. I sanded them all by hand. I think it’s easier to sand the dowel rods before you cut them into pegs because you can get a better grip on the 48″ dowel rod than on the 6″ peg! After the peg holes were drilled, I sanded the boards smooth. I sanded both sides of the boards — no random roughness around the yarn!

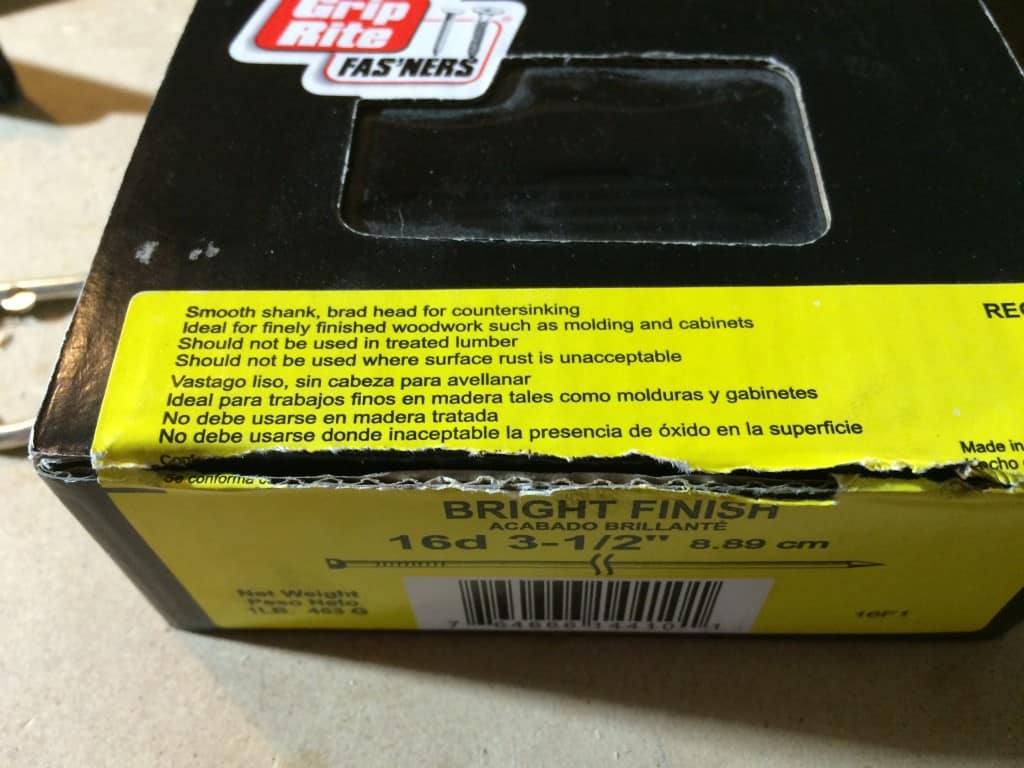

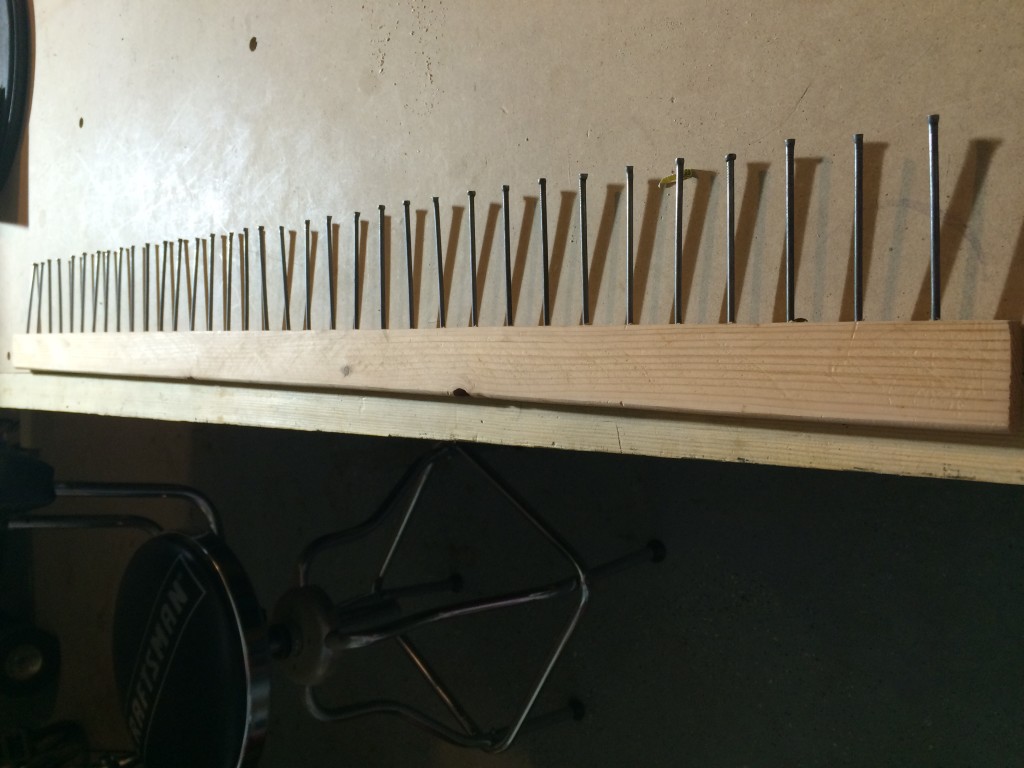

While I was sanding, Chris cut the dowel rods into 6″ lengths. The dowel rods are 48″ long, but you only get 7 pegs from one rod, not 8. This is because cutting transforms a portion of the dowel rod into sawdust, leaving the 8th peg too short. I neglected to account for this, and assumed that we would get 8 pegs from each dowel rod. We ended up having to run back to Home Depot to get another one!

The cut ends of the dowel rods get a little splintery, so I hand sanded one end of each peg after they were cut. It’s not necessary to do both ends, since one end will be glued into a hole and have no contact with the yarn.

Chris assembled the frame while I was sanding the ends of the pegs. It’s looking good!

We needed to lay the warping board flat in order to glue the pegs into the holes, so we brought it inside and laid it on our well-protected living room floor.

I glued all the pegs into the holes. Put just enough wood glue in to cover the bottom surface of the hole. Insert the peg and push down to make sure it is all the way in the hole. Most of the time, I had excess glue that pushed up and I wiped it away with a damp paper towel. Wood glue starts to set quickly. You can’t lay down glue along the entire row then go back and put in the pegs. You might be able to put glue in two or three holes at a time, depending on how fast you are! When I was putting in the pegs, we discovered that about half of them were too wide to get into the hole. I had to sand down the ends a little bit. At first I did this by hand, but I ended up using the belt sander to finish them because it was taking too long by hand.

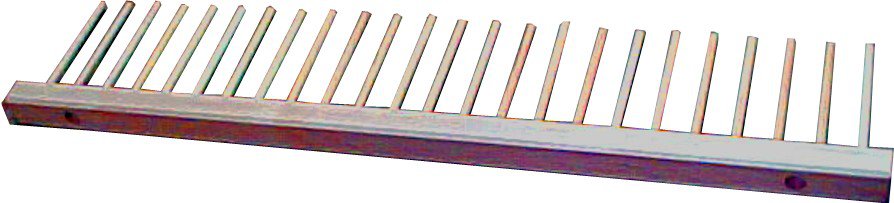

And that was it! A finished warping board!

We did not apply any finish to the warping board. You have to be careful about finishing. Do not use a varnish, which will quickly develop grooves when yarn is held under tension against it. Some people choose to finish warping boards with oil, like you would with a spinning wheel. This seemed to me like more work than it was worth, and I elected to leave the warping board unfinished.

I can’t wait to finally measure my first warp!